The Start of the Scoop

History of the Sixties Scoop

The sixties scoop started almost 300 years after colonization began. The practice of removing children from Indigenous communities without their families’ consent has existed since European settlers formed colonies here on Indigenous territories, now referred to as Canada. The Sixties Scoop is one of many examples of centuries-long government efforts to assimilate Indigenous cultures and Peoples into Canada.

‘Sixties Scoop’ refers to a process that began after 1951, as the government started to phase out mandatory residential schools. Amendments to the Indian Act meant that individual provinces now had authority over certain areas, including Indigenous child welfare. By the mid-1960s, the number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system in some provinces was over 50 times more than it had been at the beginning of the 1950s.

Decisions to place children in care at that time were made by social workers who were primarily non-Indigenous and who worked within a white-Euro-Canadian values system. Most of these workers were not familiar with the culture or history of the Indigenous communities they worked in. What they called “proper care” was based on their own lived experience rooted in a European-Canadian system of values, and training that did not include exposure to or understanding of Indigenous family structures and caregiving, nor of Indigenous worldviews and ways of knowing and being.

Social workers would seize children, without consent, often as a matter of routine, using reasoning that was deeply entrenched in racism. Observations of practices that were not typical of European-Canadian families, like traditional diets for example, resulted in loving and stable families being pulled apart. Issues like poverty and unemployment that disproportionately affect Indigenous communities due to centuries of discriminatory policies and structural violence were also seen as sufficient grounds for the apprehension of children from otherwise happy homes.

Impact

The Sixties Scoop policies are just one phase of a larger history that is characterized by physical, structural, environmental and cultural violence against Indigenous Peoples. Social workers and welfare authorities whose mandates should have been to exert a positive influence in historically under-serviced and under-resourced communities instead chose to remove children from their homes and tear families apart.

This resulted in the Survivors of the Sixties Scoop growing up with a loss of their heritage and sense of belonging. Survivors have reported that the disconnect from their culture, birth families and Nations led to feelings of confusion, isolation and shame. Survivors suffered abuse, numerous placements, and feeling of not belonging when placed in the care of the social welfare agency.

Many administrators of Sixties Scoop policies believed that removing children from their Nations at a young enough age would mean that they would not grow into their Indigenous identities. In practice, this meant that Survivors had to live through years of linguistic, spiritual and legal loss. This generation was robbed of the ability to speak their Nations’ languages, of spiritual connection to ancestral land, and, for many, of the various legal and cultural implications of having Indian status.

Many surviving adoptees reported physical, emotional and sexual abuse from the families they were placed with. Even children placed in caring homes faced emotional distress and felt a lack of belonging, as their families were unable to provide them with the cultural connections necessary for healthy development.

All of the impacts described here cannot be seen as a simple chapter of history. They are still alive today and as relevant as ever to the now-adult adoptees, their nations, their families and their descendants.

In Our Own Words

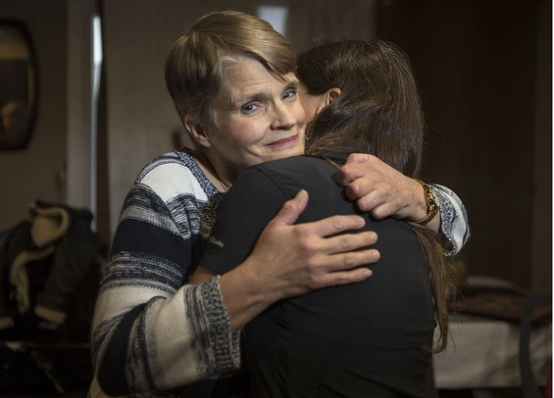

“All mama bears will attack when you try to take their cubs. Humans aren’t any different. We don’t like it when you scoop our kids. It leaves a big hole. It’s a hole that can never be plugged. It’s a sadness that never goes away.”

– 60’s Scoop Survivor Ruth Hurst

1950s: Adopt Indian Métis Program Saskatchewan

This is CBC coverage in the 1950s about the Adopt Indian Métis Program. The tone is one of positivity and makes it sound as if the children were being abandoned.

Impacts of Birth Alerts

“In Canada, an unborn child or a baby being carried in utero doesn’t have legal personhood, so it’s not legal. There’s not a mechanism for child welfare to open files on a baby that’s not yet been born. And so, the birth alert functions to create a flag in healthcare systems in places where a life giver might be giving birth that a child welfare organization has a concern about that baby’s well-being and about the life giver’s capacity to take care of them.

It might be that someone from community has called in to report a concern about the life giver or their family, or it might be that a health care provider has called in to report a concern. One of the typical ways that this might happen is if someone has been delayed in accessing prenatal care. That can happen for pretty understandable reasons, like, a fear of facing racism in prenatal care might keep people from accessing that care until later in their pregnancy. There can be a perception that they are not really attending to the needs of their baby because they haven’t accessed care.

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada put out practice guidelines for practitioners working with Indigenous women, and they said that it would be important for clinicians to know that Indigenous women might choose to terminate a pregnancy rather than carry to term for fear that their baby will be taken by child welfare.

That was really meant to make clinicians aware of how serious that fear and terror related to child welfare is and how much it impacts our reproductive health choices. I think that there’s such a gap in the system in understanding that terrorism that happens for our families, the fear around pregnancy or around accessing care for our little ones, or for our own health, especially around things like mental health, and there’s a fear that accessing care will result in the rupture of your family.

A birth alert has an impact not just in that moment, but for generations. I think to me, a birth alert, it’s like a pre-emptive triggering of that system into the life of a family.”

– Billie Allan, Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, University of Victoria

Seven Questions Answered About the Cessation of Birth Alerts in Ontario

Where Did They Go?

Where did they go? Watch this explainer video.

60s Scoop Timeline

The 60s Scoop timeline from 1909 to today.

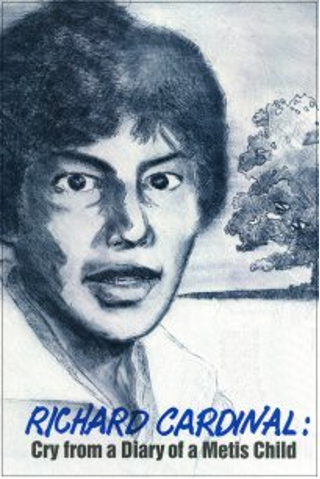

The Story of Richard Cardinal: A Cry From A Métis Child in the Welfare System

Richard Cardinal died by his own hand at the age of 17, having spent most of his life in a string of foster homes and shelters across Alberta. In this short documentary, Abenaki director Alanis Obomsawin weaves excerpts from Richard’s diary into a powerful tribute to his short life. Released in 1984—decades before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission—the film exposed the systemic neglect and mistreatment of Indigenous children in Canada’s child welfare system. Winner of the Best Documentary Award at the 1986 American Indian Film Festival, the film screened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2008 as part of an Obomsawin retrospective and continues to be shown around the world.

The Story of Richard Cardinal

The Story of Richard Cardinal: A Cry From A Métis Child in the Welfare System