Continuation of Residential Schools?

The Sixties Scoop is the catch-all name for a series of policies enacted by provincial child welfare authorities starting in the mid-1950s, which saw thousands of Indigenous children taken from their homes and families, placed in foster homes, and eventually adopted out to white families from across Canada and the United States. Children’s names, their languages, and connection to their heritage was taken. Sadly, many were also abused and made to feel ashamed of who they were.

Many women reported being pressured by doctors, nurses and social workers to give up their children shortly after birth. Mothers were coerced into leaving their babies at the hospital and private adoptions took place of new born babies to non-indigenous families. Women who voluntarily handed over their children would often be told that the arrangement was only temporary until they could “get back on their feet”. When these mothers attempted to bring their children home, they would find out the children had already been adopted.

Administrators believed that if the children were removed from their homes early enough, they wouldn’t “imprint” as Indigenous people. Much like the residential school system before it, the Sixties Scoop was part of a broader plan to force Indigenous people into the Canadian mainstream. Between 25,000 and 35,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families between the 1950s and the 1980s.

In Our Own Words

“What is home? Where is home? These are questions that often leave me reeling and wondering if I will ever feel at home spiritually and emotionally. Canada, you have made me and countless other Indigenous children and adults feel lost.”

– 60’s Scoop Survivor Christine Miskonoodinkwe Smith

Colonization

Learn how Aboriginal treaties were used to control First Nations.

A Proclamation

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763.

It established the basis for governing the North American territories surrendered by France to Britain in the Treaty of Paris, 1763, following the Seven Years’ War.

It introduced policies meant to assimilate the French population to British rule.

These policies ultimately failed and were replaced by the Quebec Act of 1774 (see also The Conquest of New France). The Royal Proclamation also set the constitutional structure for the negotiation of treaties with the Indigenous inhabitants of large sections of Canada. It is referenced in section 25 of the Constitution Act, 1982. As such, it has been labelled an “Indian Magna Carta” or an “Indian Bill of Rights.” The Proclamation also contributed to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. The Proclamation legally defined the North American interior west of the Appalachian Mountains as a vast Indigenous reserve. This angered people in the Thirteen Colonies who desired western expansion.

Iroquois Chiefs from the Six Nations Reserve reading Wampum belts in Brantford, Ontario.

Left to right: Joseph Snow, Onondaga Chief; George Henry Martin Johnson, father of Pauline Johnson, Mohawk John Buch, Onondaga; John Smoke Johnson, father of George Henry Martin Johnson, Isaac Hill, Onondaga; John Senaca Johnson, Seneca. Photograph taken at Brantford, Ontario.

Gradual Civilization Act

The Gradual Civilization Act is one of the most significant legislative events in the evolution of Canadian Indian policy. Any Indian man over the age of 21 who was able to read or write either English or French, reasonably well-educated according to the standard of the day, free of debt and of good “moral character” was eligible to apply to be enfranchised and join the Canadian body politic. Indigenous persons with a professional designation (doctor, lawyer or clergy) were automatically enfranchised regardless of whether they desired to change their legal status or not. Enfranchisement was portrayed as a highly valued privilege by the Canadian government, such that any Indian who falsely represented himself as enfranchised would receive a jail term of six months.

Enfranchisement Act

Enfranchisement was the most common of the legal processes by which Indigenous peoples lost their Indian Status under the Indian Act. The term was used both for those who gave up their status by choice, and for the much larger number of Indigenous women who lost status automatically upon marriage to Non-Status Indigenous men (see Jeannette Lavell). Only the former was entitled to take with them a share of band reserve lands and funds, but both groups lost their treaty and statutory rights as Indigenous peoples, and their right to live on the reserve community.

The aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change,” stated John A. Macdonald, in 1887.

Indian Act

In 1867, the Constitution Act assigned legislative jurisdiction to Parliament over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.” Nearly 10 years later, in 1876, the Gradual Civilization Act and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act became part of the Indian Act. Through the Department of Indian Affairs and its Indian agents, the Indian Act gave the government sweeping powers with regards to First Nations identity, political structures, governance, cultural practices and education. These powers restricted Indigenous freedoms and allowed officials to determine Indigenous rights and benefits based on “good moral character.”

The Act imposed great personal and cultural tragedy on First Nations, many of which continue to affect communities, families and individuals today. Including:

- Restricted First Nations from leaving reserve without permission from an Indian agent who was a non-indigenous person;

- Enforced enfranchisement of any First Nation admitted to university;

- Land was taken away from Indigenous people;

- Could lease out uncultivated reserve lands to non-First Nations if the new leaseholder would use it for farming or pasture;

- Forbade First Nations from forming political organizations;

- Prohibited anyone, First Nation or non-First Nation, from soliciting funds for First Nation legal claims without special license from the Superintendent General. (this 1927 amendment granted the government control over the ability of First Nations to pursue land claims);

- Prohibited the sale of alcohol to First Nations;

- Prohibited sale of ammunition to First Nations;

- Prohibited pool hall owners from allowing First Nations entrance;

- Imposed the “band council” system;

- Forbade First Nations from speaking their native language;

- Forbade First Nations from practicing their traditional and spiritual practices;

- Forbade western First Nations from appearing in any public dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant wearing traditional regalia;

- Declared potlatch and other cultural ceremonies illegal;

- Denied First Nations the right to vote;

- Created permit system to control First Nations ability to sell products from farms;

- Created under the British rule for the purpose of subjugating one race — Aboriginal Peoples;

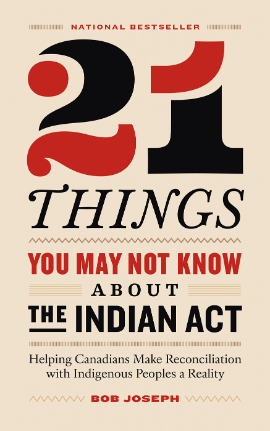

21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act

Based on a viral article, 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act is the essential guide to understanding the legal document and its repercussions on generations of Indigenous Peoples, written by a leading cultural sensitivity trainer

The Indian Act, after over 140 years, continues to shape, control, and constrain the lives and opportunities of Indigenous Peoples, and is at the root of many stereotypes that persist. Bob Joseph’s book comes at a key time in the reconciliation process, when awareness from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities is at a crescendo. Joseph explains how Indigenous Peoples can step out from under the Indian Act and return to self-government, self-determination, and self-reliance—and why doing so would result in a better country for every Canadian. He dissects the complex issues around truth and reconciliation, and clearly demonstrates why learning about the Indian Act’s cruel, enduring legacy is essential for the country to move toward true reconciliation.

In Our Own Words

“Growing up, I kind of thought, why am I this lone person and adopted into a family? Why didn’t my family want me and what were the circumstances? And as I learned that the ‘60s Scoop was actually a part of a process that started with reservations, and the Indian Act, and residential schools, and day schools”

– 60’s Scoop Survivor Leah Ballantyne